How to Win at Anything

Serious organisations, from top sports teams to Silicon Valley tech firms, now employ egg head data crunchers to uncover those magical analysable sets of measures that help them win. If you emulate just one part of this winning formula – tracking and analysing performance data – then you won’t win, because you’ll have missed the main point.

Look more closely at what game changing organisations have done and you see a more fundamental pattern than collecting and processing data. They pay attention to the assumptions they’ve been making about how to win, find evidence to test and challenge them, and they change how they do things according to what the evidence tells them.

You don’t need Prozone tracking and banks of PhD quants to do this yourself. You just need an assumption challenging, evidence based mindset to stack the deck in your favour and win more often. The principle is relevant for everyone’s job.

To illustrate how simple it is to improve by using this mindset, here are some examples with everyday games: darts, tennis and Monopoly.

Darts

Watch any player on the pub darts oche, and you’ll see a semi-wayward amateur copying the pros and aiming for treble-20. This is a great place to aim if you’re one of the 1% who’s accurate to within a centimetre from a distance of 8 feet. 20 is flanked by 1 and 5, so average players often end up with the “pub score” of 26 from their 3 darts. There are much more forgiving places to aim for anyone who isn’t an expert.

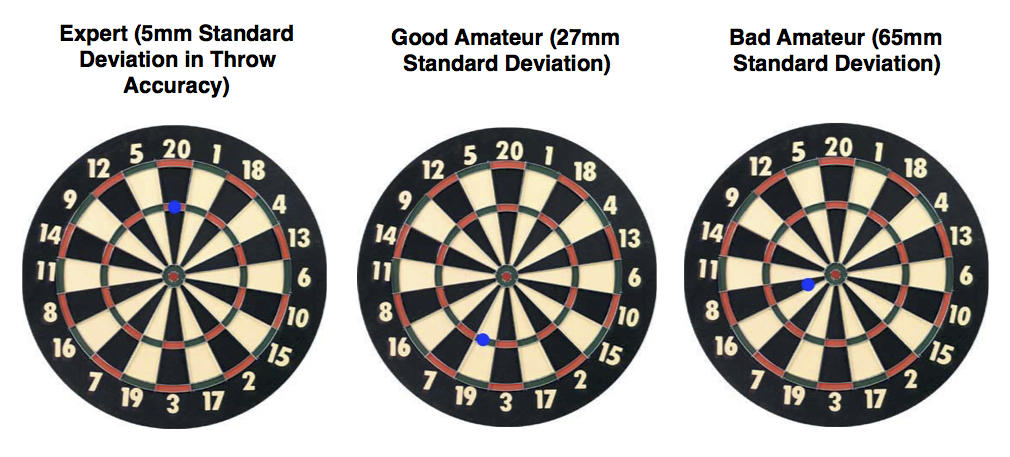

The blue dot below shows the ideal place to aim, giving highest likely score, depending on your accuracy.

There’s also an important end-game to winning at darts. I’ll leave you to work out why you should practise hitting double 16 if you’re good, but double 1 if you’re not.

Tennis

The classic measure of success in tennis is the ratio (winners ÷ unforced errors). For male pros, a good ratio is around 1, for female pros around 0.8. For amateurs, the ratio is much lower because amateurs make so many more unforced errors. So the key to winning in amateur tennis is not to go for those Hollywood passes and smashes; it’s to keep your unforced errors down, and your opponent’s up. Here are some ways research shows you can do it:

- Reduce lateral errors (i.e. the ball going out of the side lines) by hitting the ball back where it came from, i.e. return a cross court shot with a cross court shot, return a shot down the line with a shot down the line. This is because it’s difficult for amateurs to change the direction of the ball accurately, which requires the right combination of racket speed and racket inclination. You’re much more likely to be accurate if you don’t change the angle of the ball on your racket, and just send it more or less back where it came from. Obviously you need to change this up every now and again, unless another keystone of your strategy is to bore your opponent into submission.

- Reduce depth errors (hitting the net or going beyond the baseline) by practising your top spin. Because top spin causes the ball to dip, it increases the height of the window above the net you can target while keeping the ball in play. You could achieve the same by not hitting the ball as hard, but that doesn’t help you increase your opponent’s unforced errors.

An easy way to increase your opponent’s unforced errors is to target their their weaker side, usually the back hand. I’ll let you figure out how that’s entirely consistent with keeping your own unforced errors down.

Monopoly

Chances are you play Monopoly in a random, happy-go-lucky way, and maybe hanker after the ultimate of hotels on Park Lane and Mayfair. You shouldn’t do that, if you want to win. Here’s a handful of golden rules backed by a mathematical analysis of the board:

- Buy as many stations as you can – people land on stations more often than any square except jail, buying an additional station increases the value of all the others, and the rent yield is excellent

- Buy the orange streets – people land in jail 4 times more often than any other square, the orange streets are in the sweet spot of likely 2 dice totals after jail, and rent yield is excellent

- Develop houses but not hotels – the yield on additional hotel investment is poor, especially late in the game when there’s fewer turns left, and hoarding houses creates a housing shortage that stops your opponents developing

- Don’t bother with the purples (Park Lane is the least landed square on the board because of the locations of Go To Jail, Chance and Community Chest), browns (rents are still at pre-gentrified East End levels), or utilities (rent irrelevant compared to developed spaces in the mid- and end-game)

- Stay in jail at the end of the game when the rents are high

There’s a few other ways to crush your opponent, but those tips will help you dominate next Christmas. Oh, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re the top hat or the sports car.

So there’s a handful of games where you can win more often, without employing a single rocket scientist. Those were just the first three I investigated.

The key point here is to check and challenge your assumptions about how you go about something, and then make better ones based on relevant evidence:

- What assumptions are you making when you play a game or do your job, or what are you just doing without thinking about it?

- Is there a relevant source of data or evidence of how to perform better, which is relevant to you and doesn’t just copy other people with more resource or experience? The evidence in this article took me about 3 hours to find, filter and process

- If a source doesn’t exist, and if you can’t work it out, can you just design a simple DIY experiment? Do you get more power if you lower your bike seat by 2cm? Does the Jenga block come out without pulling over the tower if you tap it length wise, or pull it width wise? Do you get more responses to the same email if it’s branded and fancy or in plain text?

The metrics and rules for winning naturally change as you get better. When you start to climb up the pub darts ladder, you’ll need to start aiming at treble 20. But the principle remains the same: recognise your assumptions, challenge those assumptions with evidence, and you’ll end up with a better strategy and you’ll win more often.

Kardelen trains critical thinking, which is about being creative and complete, reasoning clearly, and challenging often dearly held assumptions.

If you want to suggest a sport or game (that hasn’t already been analysed to death) where you’d like us to challenge the evidence about how to win, just let us know.