In 1989 Sony dominated the personal music player market with 50% US market share, and still led the market in 2000 as CDs took over from cassettes. By 2008, mp3 players had become the market standard for portable music, and Apple had up to 86% share depending on which survey you looked at. Sony was nowhere. Apple did this despite being late to this market and not having a better player: in third party reviews the iPod is typically rated below Sony’s and other suppliers’ products.

To understand what went wrong, in a way that anyone could have worked out at the time with no need for wisdom in retrospect, we can use a simple logic tree.

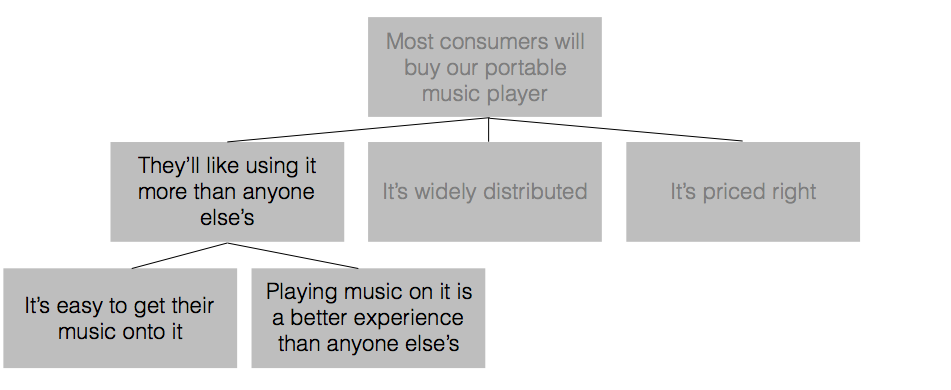

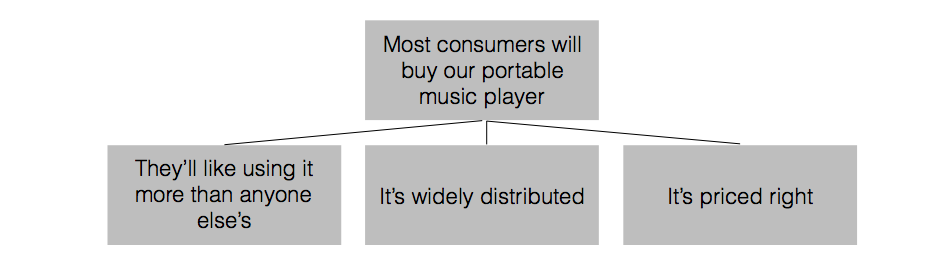

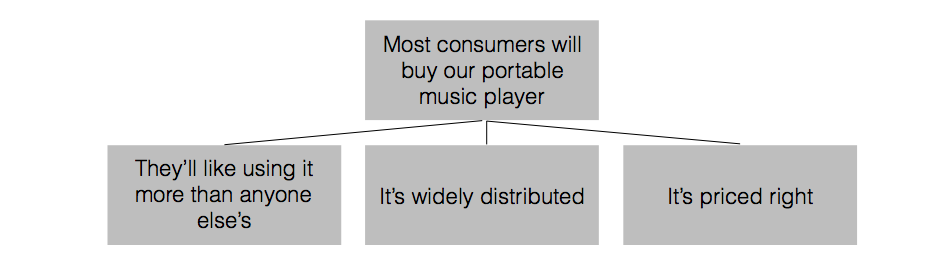

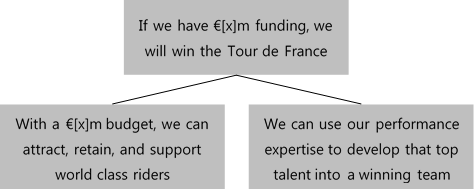

Here’s a simple logic tree that lays out the key things that need to be true for a company to dominate the portable music player market. It’s hard to argue that any of that wasn’t obvious even before mp3 was becoming a usable technology

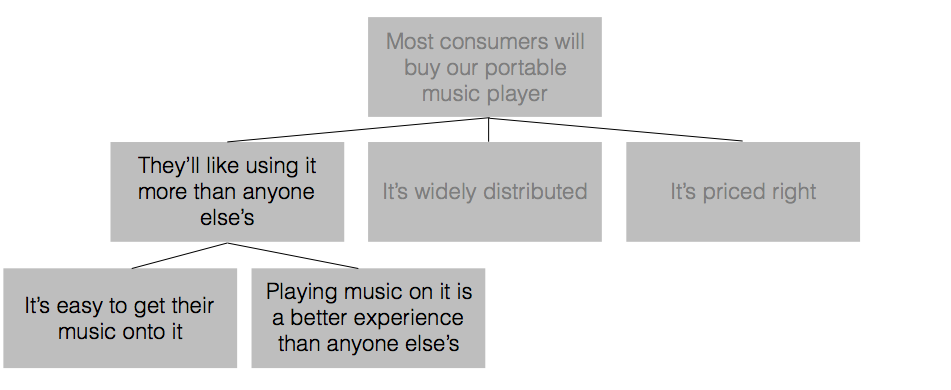

Logic trees tend to reveal useful and obvious things once you expand them, which is what happens if I expand the bottom left leg of the tree.

This bottom left hand box is where the changes happened with mp3. It was no longer just about the experience of using the player, where Sony excelled, it was also about getting your music onto it. People were no longer putting cassettes and CDs into players; they were uploading tracks from CDs, downloading them from websites, or sharing them using services like Napster. So the manufacturer’s player needed to work well with the systems used to download, store and organise music, systems like iTunes.

Apple realised the importance of the bottom left box and did something about it. It grew the iTunes library to 1.5m songs in 2 years after launch, and its devices were the only ones compatible with iTunes’ format. By 2009, iTunes consumers had downloaded 8 billion songs. These only generated ~$800m revenue for iTunes; but they made iTunes the default music management system, and that laid the ground for $22bn in sales of iPods.

It’s easy now to look back at how things turned out and be tricked into thinking that Apple must have had some overriding advantage. But Apple didn’t even have a music store until 2 years after it launched the iPod in 2001, when Sony was one of the biggest music companies in the world. So Sony had some outstanding advantages of its own. Apple just bothered to look at that bottom left hand box.

We’ve got to the heart of the matter in 2 simple steps that anyone could have taken. We haven’t created a paint by numbers solution, because those don’t exist; but we have brought our attention to the critical issue to investigate and solve. Shame for Sony, but I’m quite pleased that Apple solved it.

For a free introduction infographic about how to create a logic tree, sign up at www.kardelen.training/logic-tree/

Difficult Decisions

The people of the UK will soon need to decide if they want to leave the EU. To make this decision, each person needs to weigh up a tumble of possible consequences of staying or leaving: will they be better off, what will happen to immigration, what about security? This is the kind of judgment call, having to predict what might happen in an uncertain future, that characterises all kinds of personal and business decisions.

Folks’ natural inclination in these circumstances is to consult an expert, either in person or in an editorial column, or to fall back on some firmly held belief about how the world works. One of these approaches has a track record of diagnostic success roughly equal to a chimp throwing darts at a board containing the different scenarios, the other approach is a bit worse. But there is another way, which has a much better track record than either of these 2 common approaches.

Who Are the Best Forecasters?

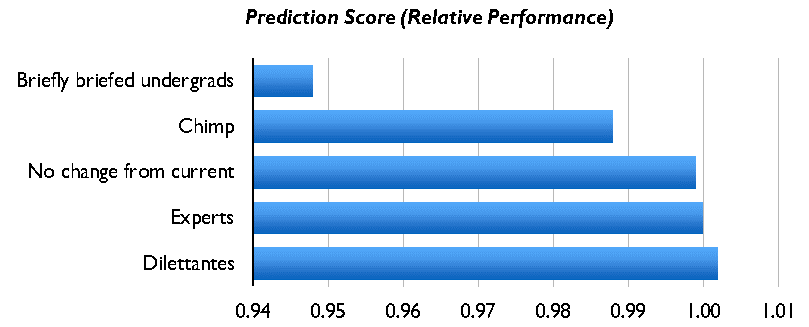

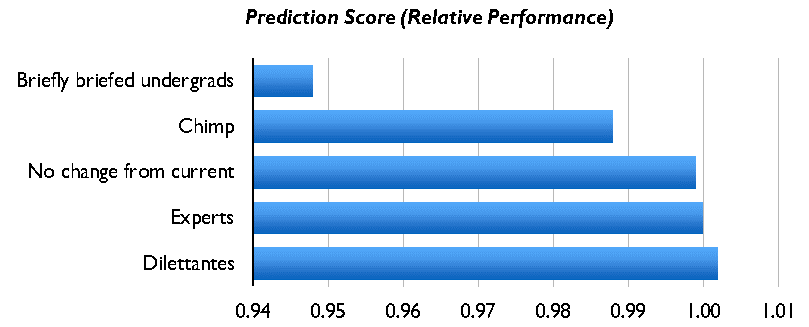

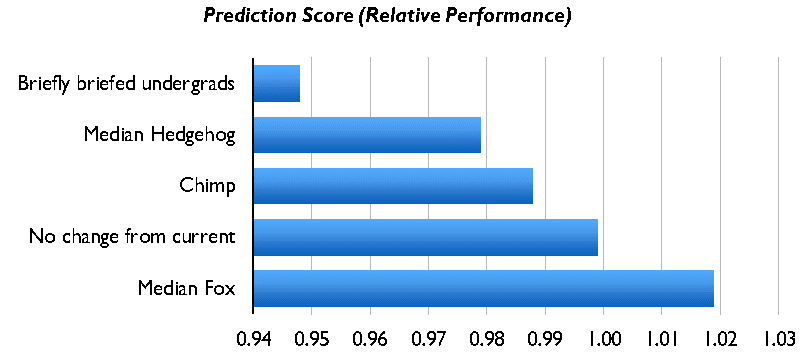

Here is an analysis[1] that tested how accurately different groups predicted a series of important political events, such as the break up of the USSR and leadership changes in a post apartheid South Africa.

The first thing to notice is that the average well-informed human’s predictions are barely better than assuming nothing changes. The second thing is that intelligent people who take time to inform themselves, or “dilettantes”, predict a bit better than experts do. Experts are typically surer of themselves and tend to be overconfident on the extremes, being more sure that something will happen when it doesn’t, and being more sure something won’t happen when it does.

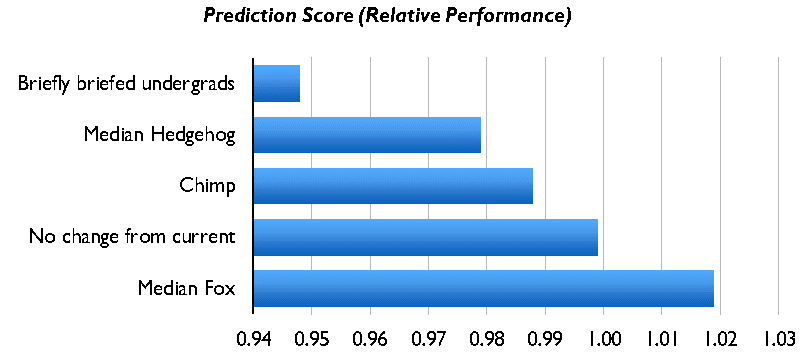

Using the same study to look deeper, at characteristics of people who make the best and worst forecasters, reveals a super useful insight. Lots of factors make no difference: age, education, technical expertise beyond a fairly basic level, political leaning, optimism versus pessimism, and idealist/realist worldview. But one trait that does distinguish good and bad forecasters is this: the willingness to consider a range of viewpoints and facts, formulating views based on that perspective and evidence rather than any pre-conceived beliefs. People with this openness are termed foxes in the study; people with more determination to stick to their worldview are termed hedgehogs. The foxes were much better forecasters than the hedgehogs.

Worryingly, those hedgehogs look like the politicians and expert ideologues filling the airwaves with elegant and consistent theories; the ones many people rely on when forming their own judgments to make important decisions. They also look like visionaries and business gurus with timeless, universal success principles. The median hedgehog is worse at judging outcomes of important events than a dart throwing chimp.

So How do Good Forecasters do it?

In an ongoing real life study[2], volunteer dilettantes, who work just like the foxes in the previous study, have outperformed every other competitor group in formal forecasting competitions, including university departments and government intelligence analysts with access to privileged information. They don’t just beat every competitor, they beat them easily, every year. These “superforecasters” have no specialist expertise; their only common factor is their mindset and a common approach:

- Clearly define the problem, being careful not to substitute it for an easier one

- Break this bigger problem down into components small enough to analyse clearly

- Use the best, most relevant external data, and internal reasoning, to test each component

- Share that reasoning and evidence with other people to test whether it is robust, whether you’ve missed or misunderstood anything, inviting challenges and improvements

- Adjust the answer as relevant new evidence emerges

- Once the event has come to pass, measure and get feedback about how accurate you have been, learn, and adjust for next time

If this looks to you like good critical thinking that anyone can learn, that’s because it is. It doesn’t require genius, years of specialist subject matter expertise, privileged inside information, or any secret formulas. Good, robust critical thinking just needs a disposition to be open and challenge, some simple training and a bit of regular practice.

For a free introduction to critical thinking, sign up at www.kardelen.training/logic-tree/

[1] Expert Political Judgment, Philip Tetlock, , 2005. I have changed the term “Contemporary base rate” to “No change from current” to ease understanding. I also excluded tested models (cautious case specific extrapolations, aggressive case specific extrapolations, and autoregressive distributed lag models), which perform better than humans where they are available

[2] Superforecasting: The Art & Science of Prediction, Philip Tetlock & Dan Gardner, 2015

In 2008, British Cycling’s Performance Director wanted to create a professional road cycling team, and needed to pull together a plan to take to a potential backer for funding.

The idea was simple: a Pro Tour level cycling team needs a budget of €[x]m; if we add in our world leading performance expertise, we can win the Tour de France.

Applying some critical thinking before launching into a plan flipped this simple idea around, and made getting the budget right as important as any of management’s performance expertise.

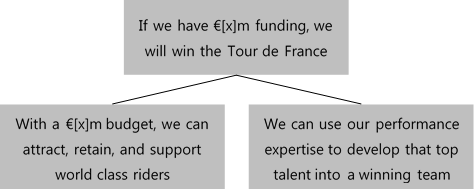

Taking the premise “We will win the Tour de France,” a simple logic tree clarified what needed to be true for this great achievement to happen. Here’s the tree:

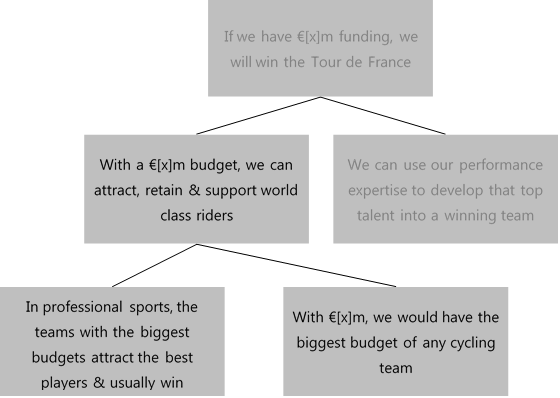

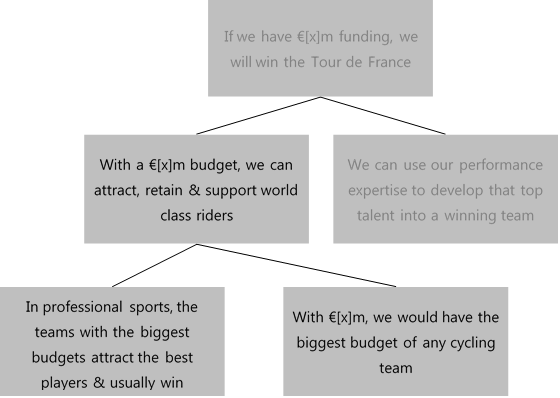

Both legs of the logic tree need to be true to achieve the goal of winning the Tour de France. The right leg is about faith in a management team that wins gold medals, and whether their expertise can be transferred into winning on French roads. The left leg is where the new insight came so I’ve expanded it here:

That box at the bottom left is the insight that makes all the difference. In professional sports teams, unlike national and Olympic teams, the players can move if the money isn’t good enough. Looking across dozens of professional sports, including road cycling, there is solid evidence that to attract and retain the top talent, and to win the biggest prizes, the team needs to be one of those with the most money. As many sports teams have learned, you can have the best youth academy and coaching methods in the world, but the top players or riders will leave if they aren’t rewarded like their world class peers.

So it was essential to investigate the budgets of the other top teams, including the salaries of all the riders; and check the costs needed to pay the best salaries, as well as to have the best facilities and support. Adding everything up, and working out what was needed to be the best funded team, made the €[x]m funding requirement a lot bigger than it had been before anyone started sketching out logic trees.

So What?

You could look at the tree and say “that’s obvious.” Well that’s how it should be. Drawing out a clear logic tree reveals important things in an obvious way. The main point – to win you need the most money – wasn’t obvious to anyone before some simple thinking brought it to everyone’s attention.

Laying out this clear reasoning and supplying the evidence also made things very obvious to Sky Sports, the company that was putting up the cash. They wanted to have a good chance of winning the Tour de France; they agreed with the thinking, understood the evidence, and believed in management’s ability to make it all happen, so they made the Team Sky the best funded team in the sport.

Obviously, a budget doesn’t ride a bicycle up giant French mountains. The Tour de France was won by the riders and the team supporting them, not by a logic tree and the associated business plan. The clear critical thinking using a simple logic tree just helped the team get enough money to pay for all the blood, sweat and tears; and it gave Sky some justified confidence that it was going to be money well spent.

For a free introduction infographic about how to create a logic tree, sign up at www.kardelen.training/logic-tree/