Dealing with Frightening Research Findings

All of us, quite often, find ourselves on the wrong end of troubling research findings, from analysts, subject matter experts, and marketeers. Such findings can lead us to change something drastically or just worry a lot. We’re commonly not in a position to challenge how well the research behind the findings was done, and whether the conclusions are actually correct. In these situations, we can almost always change how we decide to act on those frightening findings, and usually lower our heart rates, if we ask a simple question:

“OK, if I assume these findings are true, what do they really mean for me?”

We can do this with zero subject matter expertise, and usually quite quickly.

Let’s do this with a recent news release from the World Health Organisation’s cancer agency, the IARC, which scared the bejesus out of meat eaters.

IARC Frightens Carnivores with Scary Headline

The IARC news release said that processed meat caused colorectal cancer and that red meat probably did too. The release contained just 1 piece of data: every 50g of processed meat eaten daily increases the odds of contracting colorectal cancer by 18%.

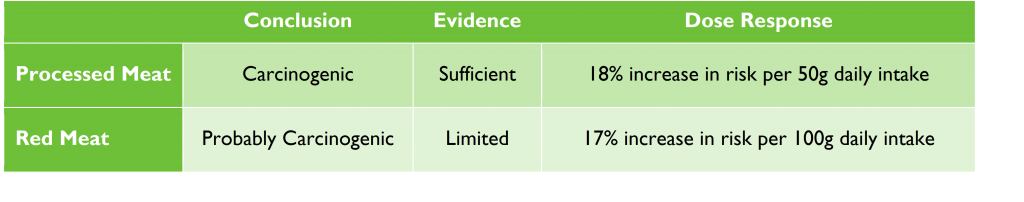

Here are the conclusions behind the headline:

The broader conclusions, as usual, are a bit less sensational than the headline, particularly for red meat given its limited evidence of harm. Still cause for concern though: sounds like eating not very much increases our chances of dying young by quite a lot.

So let’s check what these findings mean for us. To do this we need to put everything in context – what we mean by red and processed meat, how much is 50-100g, and what a 17-18% increased risk really means. Then we need to ask what happens if we do and don’t follow the implied advice.

Sweeping Definitions that Cause Uncertainty

Let’s get clear about what the IARC means when it says red and processed meat because those groups sound a bit broad. Its red meat research doesn’t distinguish between a slow-cooked organically raised local lamb stew, and a minced burger that’s fried in oil, comes between 2 slices of sugar enhanced bread, and is served with fries and a cola. Its processed meat research doesn’t distinguish between traditionally cured Serrano ham and a scotch egg.

We’ve only looked at definitions, but intuitively we’re already probably a bit less worried if we’re home cooking foodies or paleo warriors.

But let’s be prudent in this case and assume the findings apply to all the processed and red meat that we eat with no exceptions, from steak tartare to kebabs.

Small Looking Numbers that are Really Large

Let’s look at that small sounding extra 50g of processed meat or 100g of red meat.

The average person who eats red meat consumes 50-100g per day, and heavy red meat eaters eat more than 200g per day. Apparently there aren’t reliable numbers on processed meat. So eating that small sounding extra 50-100g means doubling your intake if you’re an average Joe; and cutting down by 50-100g means cutting it out entirely. So changing by 50-100g isn’t a small amount, it’s a lot unless you’re a major carnivore.

The critical thinking alarm bell here was the 50-100g number being presented as an average daily amount. If it had been weekly (half a kilo) or monthly (1.5-3 kilos), then it would sound like the large amount it is. No wonder those mobile phone salesmen always convert the insurance cost into a few pence per day.

Large Looking Percentages that Don’t Amount to Much

Now let’s look at the effect of doubling your intake, and that scary 18% uplift in your chances of getting colorectal cancer.

When faced with large percentage increases or decreases, we have another critical thinking alarm bell going off and a typically very useful question: “An increase from what to what?”

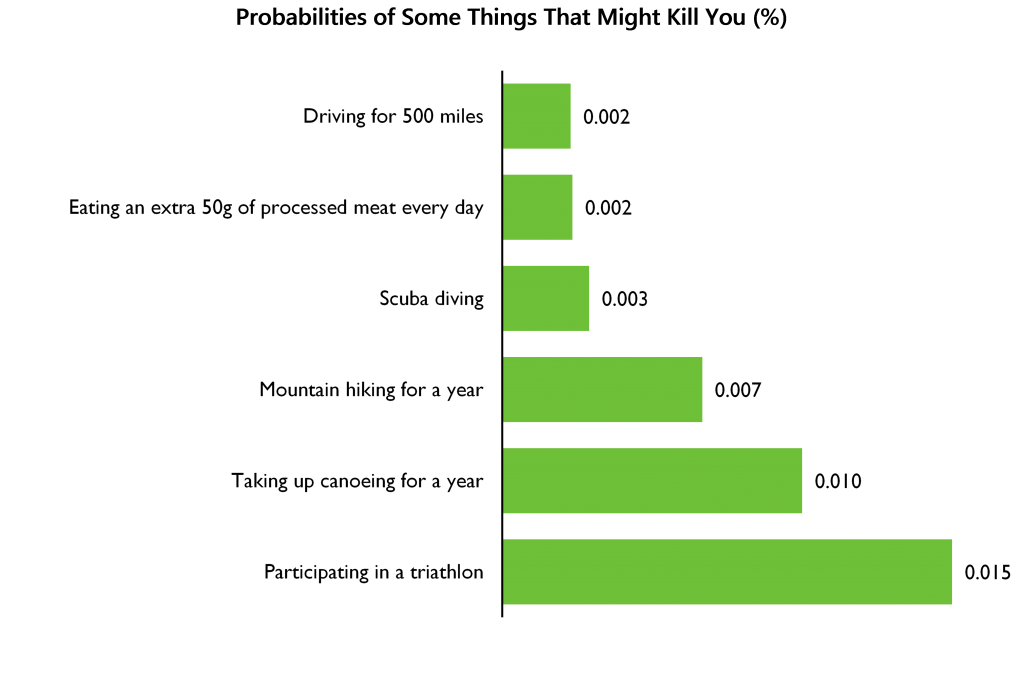

Currently, the odds of mortality from colorectal cancer are about 1 in 8,000 in developed countries. An 18% uplift gives you an extra 1 in 45,000 risk of mortality, or 0.002%. To make these numbers meaningful, here are some activities with an equivalent risk of mortality.

Just don’t compound your risk by driving 500 miles to a triathlon, and eating more pork pies on the way home to refuel.

What if I Follow the Advice, and What if I Don’t?

What if I take the advice and cut out processed meat? I haven’t cleansed myself of the risk of death from colorectal cancer; I’ve just lengthened the odds from 1 in 8,000 to 1 in 9,000.

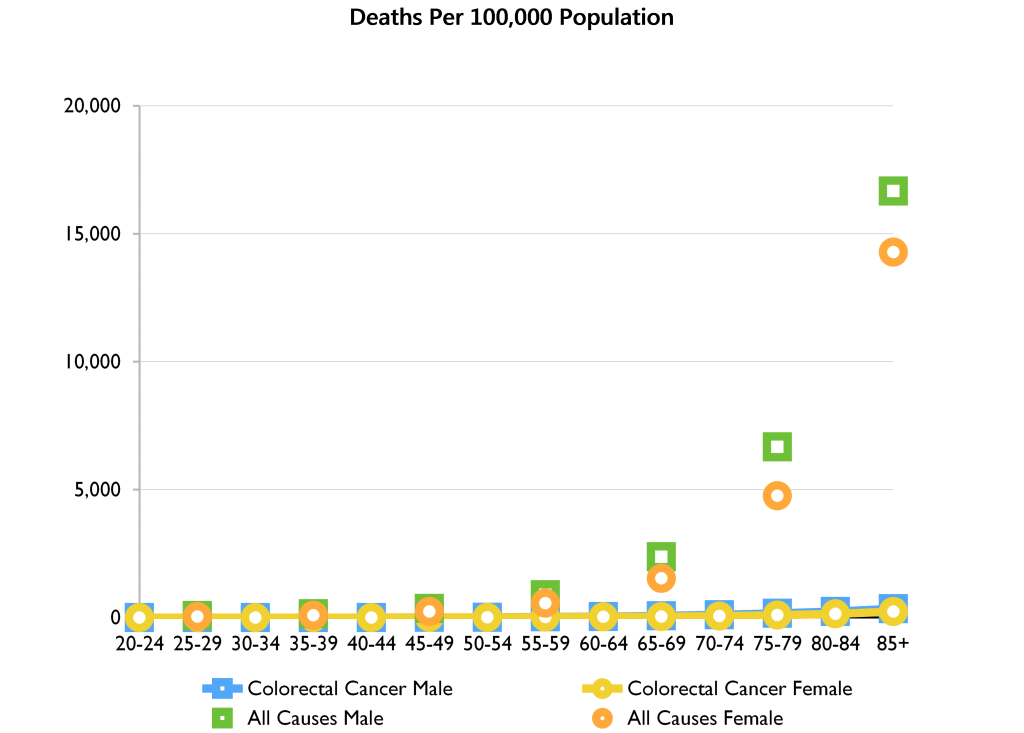

OK, what if I ignore the findings and keep eating those delicious salt beef sandwiches? I might get colorectal cancer, but there’s a much, much higher risk that something else will get me first. Here’s the risk of death by colorectal cancer versus other all causes for different age groups.

OK, So What?

So here’s my reinterpretation of the IARC news, having just checked what the findings actually said and put everything in context. Eating a lot more processed meat would increase my risk of colorectal cancer by double digit percentages from not very much at all to still not very much at all; and I don’t seem to have strong reasons to believe that eating simply-cooked unprocessed beef or lamb will do me any material harm. This is very different from the original message from a high profile and widely trusted organisation.

We didn’t need any subject matter expertise in oncology to superimpose some sanity and perspective onto this frightening headline; we just needed some basic critical thinking to ask what findings really mean if they’re true. If we can use such simple clear thinking to add a much more balanced context to the work of rigorous scientists; think how we can use it to contextualise similarly startling insights from the less balanced world of business presentations, magazine articles, and pronouncements of gurus.

For me, I’m confident this article will increase my cumulative page views by at least 20%, will be my #1 health related post, and will retain my 100% publication track record. I’m getting all that benefit from barely 10 minutes of research and writing per day.