Discomfort = Skepticism

You read a headline that smart TVs emit radiation that is perfectly safe. What do you do? Nothing, right? It makes sense and there’s nothing to worry about.

What if the headline said that smart TVs emit radiation that’s deadly for anyone watching more than 15 minutes a day for 7 years. Would you accept those findings just as easily, chucking out your TV as a minor sacrifice compared to your good health? I reckon that maybe you’d actually read the report under the headline, understand what the research actually said, check how credible it is, and even find out if any other experts agree or disagree, before visiting the recycling centre.

When we like what we’re hearing we’re accepting folk, happy with simple sense checks. When we don’t like it, we morph into frigidly analytical arch-skeptics.

Fooling Students with Yellow Paper

In a famous study, participants were told to put their saliva on yellow litmus paper that would turn green within one minute if they had the, invented, condition of TAA deficiency. The “litmus” paper was just yellow paper that would never change colour.

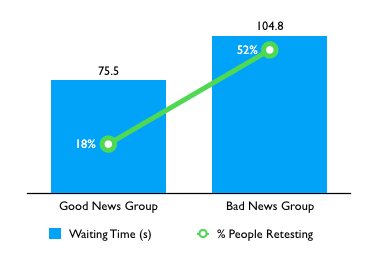

One group (the good news group) was told the paper would turn green if they had TAA deficiency. The other (the bad news group) was told staying yellow meant they had the condition. Here’s how the different groups behaved:

The good news group did obediently wait over a minute until they were happy the yellow paper wasn’t going to change colour. The unfortunates who were told yellow paper meant TAA deficiency just waited and waited for that paper to turn green and give them better news. More than half of that group with the fake bad news also tried a retest.

The group getting the bad news was also more dismissive of how serious TAA was as a condition, imagined it was more common, thought the test was less accurate, and in a follow up could be prompted come up with far more mitigating life irregularities that rendered the test less reliable.

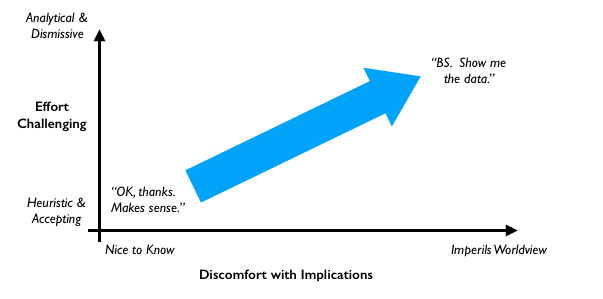

This happy acceptance of things we want to hear, but motivated skepticism about what we don’t is strongly influenced by knowledge and intelligence, in a bad way. Research shows that the more intelligent, numerate, informed and expert we are, the better we are at finding reasons to support our desired worldview and reject what we don’t like.

So What?

Rather than bemoaning how bonkers and irrational people are, I think this information is pretty useful in helping us make better decisions and in persuading people to a bit more open. The place to start is in the mirror.

I’m not arguing that we mimic French philosophers, challenging each treasured belief in turn, pulverising our worldview and indulging in a self motivated existential crisis. What I am arguing is that when we’re faced with a big decision – like starting a venture, taking a job offer, or hiring a candidate – we switch around the burden of proof from its usual place of “convince me that I’m wrong.” The burden of proof should now be squarely on your dearly held belief, for example that your cat millinery hobby can be turned into a business, that the job with the hipster beard accessories start up is right for you, or that you should give the job to the candidate who’s most buff and shares your love of televised sport. Evidence shows that this mindset of prompting ourselves to be analytical actually does work.

Evidence also shows that people are much more objectively analytical in groups, which is a good reason to rope in that peer reviewer, devil’s advocate or challenging mate. This is uncomfortable, but in you’ll make a better decision by caring about the truth than by sheltering your beautiful worldview from harm. And once you’ve made the decision, you’ll actually have more confidence from having challenged things hard.

Persuading others is a whole new bagful of monkeys. But once we accept that people are motivated skeptics, we realise there’s wisdom in choosing who to persuade and choosing whether and how you persuade them.

- You’re miles ahead if you can work with people who are predisposed to you and what you’re going to say. This is one reason why management consultancies sell to their alumni, and why football managers are all former players.

- When you need to step out of your echo chamber of like-minded folk, but still have a choice between trying to persuade someone whose views are opposite to yours, or someone who’s open minded, go for the swing voter every time.

- If your thankless task is to persuade someone who has a strong opposing dearly held belief, don’t fool yourself that a selection of facts and a cogent argument that goes head on with theirs will have any effect other than to entrench them. When people disbelieve they get analytical, so emotional appeals won’t help either.

With these folks, the data suggests a couple of things. First, focus on insights they might not have considered and where they don’t have a foundation to rudely undermine. For example, one purported reason there’s fewer girls than boys in technical subjects is that girls are as good as boys at technical subjects but better than boys in the other school subjects; so boys focus on the technical stuff, and girls are spread across the full range of subjects. This feels like a more productive place to have a discussion about why your computer course doesn’t get enough women on it than some potential misogyny spiral.

And the next time you’re questioning the quality and justice of the referee’s every decision against your team but not really giving that much thought to those calls that go your way, or muttering about the media’s right/left wing bias, give yourself a nod of recognition – that’s your own highly motivated skeptic hard at work as usual.