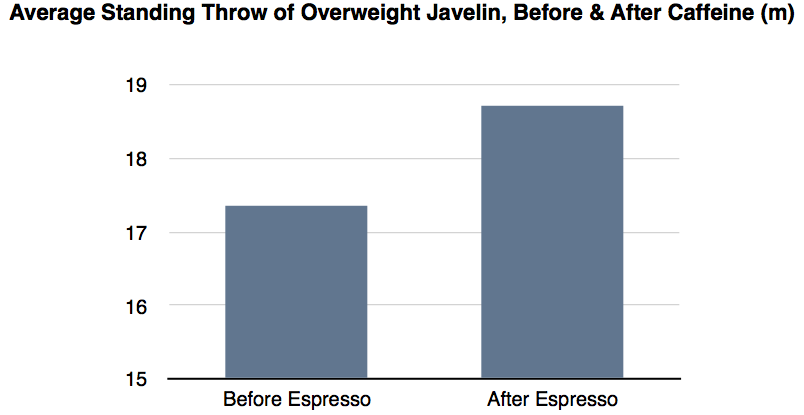

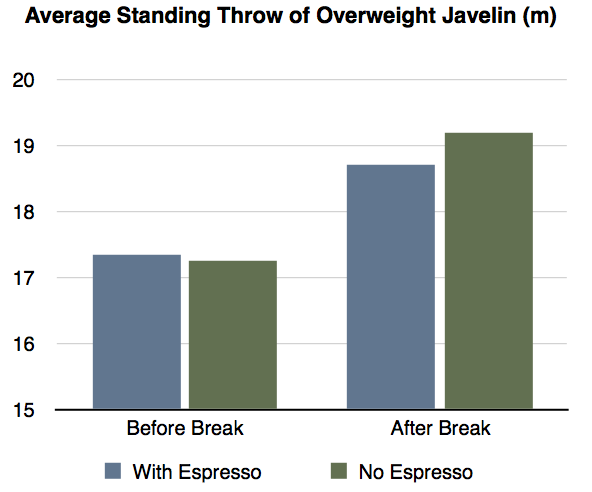

Here’s an obvious improvement, and a clear cause of that improvement.

The stimulus of the espresso really caused an improvement in the javelin throw. More evidence for the performance enhancing benefits of caffeine? Not so fast.

What Caused What?

If we see one thing happen (A) and another thing happen (B) we can conclude at least 5 different things:

1. A caused B. My singing (A) caused my singing teacher to wince (B).

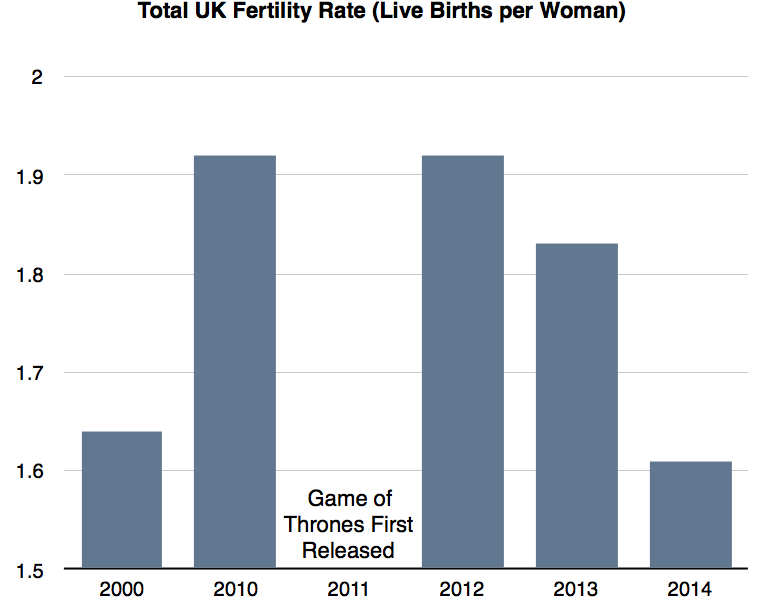

2. Something else caused B. Here’s an analysis of UK fertility rates (B) before and after Games of Thrones (A) was released on HBO in 2011. Anyone arguing that GoT caused a decrease in birth rates, Khaleesi?

3. Something else caused both A and B. If shark attacks (B) go up at the same time as ice cream sales (A) on US and Australian beaches do we conclude that those ice cream sellers are tempting in the sharks, or maybe that hot days cause more people to go the beach and in the sea?

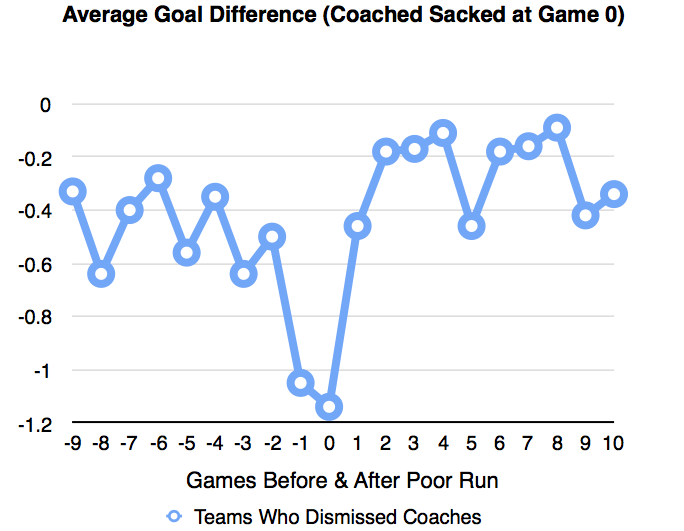

4. The change in B was random. Here’s one time we can feel sorry for football managers. Take a look at this excellent German research on football teams’ results (B) when they had a bad run of form and changed manager (A). Looks like changing the manager was a good idea.

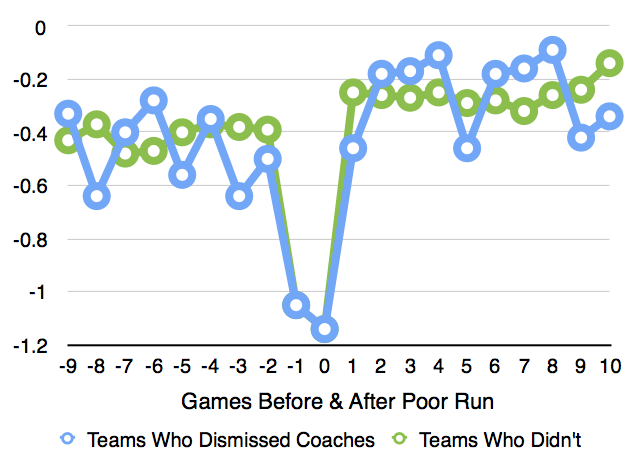

Now have a look at the teams that had similar dips in form but didn’t change manager. Do you still think changing the manager made a difference? Or that teams just revert to their typical performances following a bit of bad luck?

5. B caused A. Did our change in manager (A) cause a change in performance (B), or did a run of bad performances (B) cause a change in manager (B)? Does veganism (A) cause better health (B) or are health conscious people (B) more likely to become vegan (A)?

How to Tell if You Have Your a Cause

In most, complicated, real life circumstances the way to know you have your cause is to find yourself 2 almost identical situations: in 1 the cause being present; in the other absent.

We can see if these 2 situations already happened in the real world, just like our German football teams that did change manager after a bad run compared to those that didn’t.

We can also create these 2 situations by doing our own trial, to see what happens in when our speculated cause is present versus when it’s absent. Here again is my experiment of throwing the javelin, this time showing before and after a break that didn’t involve drinking espresso.

Looks like the espresso isn’t the cause of the improvement after all. Maybe it’s just that a good warm up and practice causes better performance.

Even if you think you have a cause, here’s a few other tests that’ll raise your confidence that you really do:

- Can the effect be obviously explained by anything else? Are ulcers obviously caused by stress, or could it be something else, say, H Pylori?

- Does the effect happen every time the cause is applied? Does hiring Pep Guardiola cause your football team to tiki-taka its way to the Championship? Yes, well except when it doesn’t.

- Is there a low chance of the cause effect being explained by randomness? Run lots of

experiments on small enough samples and you’ll find lots of fascinating counter-intuitive cause effect relationships that no one will ever replicate. - Are our sample groups similar? If we only give training to super stars on the promotion fast track,we can’t compare its effect against a sample of regular folk who aren’t on the fast track.

- Is there a chance that the participant is wittingly or unwittingly fixing the outcome? Would you trust the findings of a sports drink company about the big race time improvements that come from drinking its product?

We will all sometimes jump to conclude that our management intervention caused our temporarily underperforming branch to improve, that people are successful because they say “no” more often and not the other way around, or that our team lost because we weren’t wearing our lucky jumper. If it’s important, that’s the time it’s worth reflecting on whether we really do know what’s a cause and what, well, isn’t. If we don’t, we’ll be drinking too much espresso and not doing enough javelin practice.