It’s OK if Your First Idea is Wrong

When you’re trying to solve a problem, there’s usually not a whole lot of difference between right and wrong answers. More often than not, as long as you start somewhere, recognising that it’s probably wrong, and spend time tinkering, you’ll get to right.

Here’s an example. I want to dominate next year’s amateur Tour de Snowdonia with its massive climbs and mountain top finishes. So I figure I need to hit the weight room six times a week, and squat an extra quarter kilo each session to end up with stronger legs than The Mountain from Game of Thrones.

I can test whether my theory is right or wrong with some simple checks.

- Completeness: Does my thinking cover everything important? Not here, because being lean is just as important as having super powerful butt and thigh muscles, just look at those skinny devils who win the big Tour de France climbs

- Assumptions: Have I made correct assumptions? No again. If you’ve ever been to the weight room and tried your hardest every day for 6 days in a row, you know you just get weak and tired. You need the odd day off to recover

- Valid reasoning: Does my reasoning make sense? And no again. I don’t need the strongest thighs (or leanest body) in the world, I just need to be better than my opponents.

And there’s an essential final check to my solution: I’ve got the ability to test whether I’m right or wrong, by climbing on my bike and seeing how quickly I get to the top.

My initial thinking was wrong, but that’s fine because I can now tinker and make it better – I can take a bit of weight off, build in some recovery, and work out how good I need to be at climbing to win. I can check all this by riding up the hills. I needed to go through wrong to get to right.

If You’re Not Even Wrong There’s Nowhere to Go

Where I’m really in trouble is when I’m not even wrong[1]: when my thinking is so far off the mark that I don’t know where to start or whether to even bother testing. You can tell when someone else is not even wrong by your immediate reaction of “Huh? Say again.” Here’s how to tell if you’re guilty of it yourself.

- Completeness: Your thinking is narrow so you miss the critical points: “We should reinforce the returning planes in the wings, where the bullet holes are.” (How about where the holes might have been in the planes that didn’t return?)

- Assumptions: I’ve made some monumentally naive or crazy assumption, probably because I lack subject matter expertise: “Clearly the best song is going to win Eurovision.”

- Valid reasoning: My reasoning is so vague or twisted or odd that it’s hard to know what the reasoning is, or how to challenge it: “We’d be twice as democratic if we held a second referendum.”

If we’re not even wrong like this, we can’t build on our first answer and get to a better one. There’s nothing to build on. It’s best just to screw up the paper with our sketched solution, throw it in the bin, and start again.

Deliberate Not Even Wrong

The most heinous critical thinking crime of all is when someone is deliberately not even wrong, which happens a lot. With deliberate not even wrong your immediate reaction is, “I see what you did there you sneaky little rascal.”

Leaving aside clever argument sophistry, there’s a whole list of everyday not even wrong tactics that we all employ. Most of these are ploys to avoid being tested and, ironically, being wrong:

- Excuses – “I would have been right about Kayley winning Bake Off if they’d given her the score she deserved for her 3-tier Waffle House.”

- Hedging – “That 1 room Kensington apartment is a bargain, if prices keep rising by 10% year.”

- Vagueness – “She’ll get the results her performance deserves.”

- Circular reasoning – “It’s a close call, but I predict the winners are going to be the team that best rises to the occasion.”

- Inability to disprove – “His desire for control all comes from his unconscious feelings about his mother.”

- Downward sloping shoulders – “I’m happy with it if you are big fella.”

Of course, we shouldn’t be naïve. If lawyers might be circling, then we need a disclaimer.

But if we want to have a good chance of getting to a right answer, we need to start with something that passes all our checks: it attempts to be complete, has decent assumptions and valid reasoning, and we can test it. If we start out by being not even wrong, deliberately or otherwise, then we’re in a cul-de-sac to nowhere.

[1] This doesn’t apply to matters of faith, taste, intuition etc, it’s just where you’re attempting to be in some way rational or scientific

If you want to know if someone’s stated reasons for doing something are true, there’s no point asking them. There are much better ways of finding out.

Bootleggers & Baptists

Bootleggers and baptists is a catch phrase to characterise how you can get one morally righteous group fronting something, while another group quietly benefits. The reference comes from US prohibition, when baptists lobbied for restrictions on selling alcohol, while bootleggers profited nicely.

It’s all too easy for a bootlegger to dress himself up as a baptist when he’s trying to get his way. So if we’re going to judge someone’s moral argument, we need to know if we’re dealing with a baptist or a bootlegger[1]. If we take them at face value or ask them, they’ll just answer as a baptist. But if we think a bit more clearly, we’ll get to the bottom of it.

One baptist argument being spouted here in England is by the RMT rail union. The RMT doesn’t want a train company to install monitoring technology that enables drivers to open and close the doors. This does away with one of the roles of the train conductor, and according to the RMT it threatens passenger safety. The RMT called a strike this week to stop driver operated doors and protect passenger safety.

So is the RMT a baptist (champion of passenger safety), a bootlegger[2] (champion of RMT members), or both? Let’s have look.

Is There a Bootlegger Benefit?

Faced with a baptist pronouncement, asking “who benefits?” can help us work out if there might also be a bootlegger. The RMT calls a strike to stop driver only train operation. Its members are train conductors, whose jobs might be threatened by the change. They benefit if the driver only trains are stopped. Could they be bootleggers?

Asking “who benefits?” doesn’t tell us the RMT is a bootlegger, but it tells us it might be.

Does a Neutral Expert Support the Argument?

There’s obviously no point asking a potential bootlegger about his expert opinion on the matter. There’s also no point asking any old expert whether an argument is true. It needs to be someone without a dog in the fight.

Do you believe the RMT’s claims that driver only operated trains are less safe? Would you believe the train company’s expert opinion? Or do you believe the Rail Safety & Standards Board, which says that there are plenty of driver only operated trains and they’re just as safe as conductor operated ones?

The least biased view seems to be saying that safety isn’t a big issue here. The neutral expert rejects the baptist argument. I sense a bootlegger.

When Do They Act?

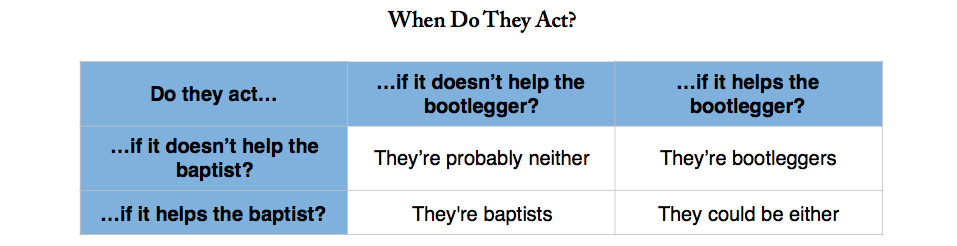

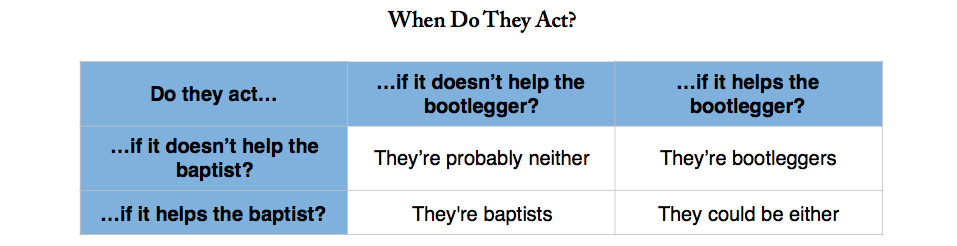

Though we shouldn’t take baptists’ words at face value, we can learn a lot from how they’ve acted. Have they ever acted in a way that a would benefit baptist but a not bootlegger? Have they acted in a way that would help a bootlegger but not a baptist? How about when neither would benefit?

Here’s how to tell what they are from how they behave:

Let’s look at our RMT strikers again and how they’ve acted in the past. Have they ever gone on strike for an issue that was purely about job security or pay and conditions but not about safety or some other baptist cause? Yes, that’s the reason given for most of RMT’s strikes. That’s squarely in our top right box. They’re bootleggers.

Just as useful is to look at when someone doesn’t act. Do they stay in the background when a baptist would act? Do they do nothing when a bootlegger would act?

Let’s have another look at our RMT strikers. Have they gone on strike about issues that threatened safety but didn’t affect members jobs, for example the fairly well accepted problem of trespassers on tracks? Not that I can find. They’re not in our bottom left box. They’re not baptists.

Bootleggers Pretend to be Baptists Everywhere, and We’re Onto Them

We’ve used some simple clear thinking to call out the RMT on its pretence that the strike was all about safety. This isn’t to attack unions. Faced with a choice between a union and a monopoly, I’m on the union’s side every time. I just want them to be frank about their motivations.

The bigger picture is that bootleggers everywhere either stay quiet or posture morally and pretend to be baptists. The Chancellor raises alcohol tax to promote responsible drinking – is the Treasury a bootlegger? The Ministry of Defence buys British – are its senior staff, who commonly move into the private sector to work for British Aerospace, bootleggers?

You won’t tell who’s who by listening to what they say about themselves or to their own experts’ declarations. To find out what their real motivations are you need to think about who stands to gain, listen to people without a dog in the fight, and to pay attention to how they do and don’t act.

[1] I want to be clear that I’m not using bootlegger as a pejorative term. I can relate just as much to rascal (non-mobster) bootleggers as holy baptists. My mission is to call out baptists when they’re baptists, bootleggers when they’re bootleggers, and both when they’re both.

[2] This isn’t a union bashing or promoting article. Unions at their simplest are labour cartels that in most countries are effective negotiating counter parties in industries with monopoly employers. Judging by wages and employment conditions in those sectors, unions do a fine job of this