With the BBC’s status apparently under threat from the Tories, various people connected with the BBC have naturally come out to explain what a unique and valuable institution they think it is. One of these people is Steven Moffat, producer of the highly acclaimed Sherlock, and of the new series of Dr Who. Here’s a couple of extracts from a Guardian article covering his speech:

“It’s fair to say that there’s only one broadcaster in the whole world that would have come up with and transmitted as good an idea as Doctor Who…” [said Moffat]

Along with the Great British Bake Off and “everything David Attenborough has ever done”, Who is a wonderful example of the corporation’s breadth, according to Moffatt. “There is no other broadcaster so madly varied and so genuinely mad,” he said. “Can you imagine what the world would be like without that insane variety?”

There’s a few things that make it difficult to form a judgement from this article, and use it as a basis to give the thumbs up or down about the BBC being a good thing:

- He’s only talked about the benefits of the BBC; and we can’t conclude it’s a good idea without also thinking about its costs. My home town club Blackburn Rovers would really benefit from having the entire Real Madrid team turn out for them on a Saturday, if we didn’t have to worry about those cursed transfer fees and annoying player salaries

- His argument in the article is based on a few examples, which is a common way of arguing, and is good and memorable and easy to visualise, but he’s given us no solid data to back up his general claim of world leading excellence and variety. For we critical thinkers, this sets off a little alarm bell: “Is he just cherry picking the good stuff?”

- His point about variety sounds like a red herring unless we take a moment to think about why variety is important. Does it actually matter if one big production company has a lot of variety, if the same types of things are being produced by lots of other companies big or small?

There’s other things about the argument that would make a logic buster twitchy, but I’ll stop at the 3 above.

Just because he’s not making his points in a perfectly balanced way – he’s promoting a cause after all – it doesn’t mean he’s wrong. So let’s look at his argument. We’ll confine our investigation to testing what he claims in the article, leaving aside the costs, and any other arguments for or against the BBC.

To have something tangible to get our teeth into, we need to clear up what he’s claiming. We need to do that in a fair way that’s generous to the spirit of what we think he meant, but also in a way we can test with evidence. Here’s what I come up with if I do that:

- The BBC produces some of the best TV programmes in the world, and more than its fair share of all high quality TV programmes

- The BBC produces a broad range of different types of high quality programmes, including some types that all the other TV companies put together don’t cover anywhere near as well as the BBC does

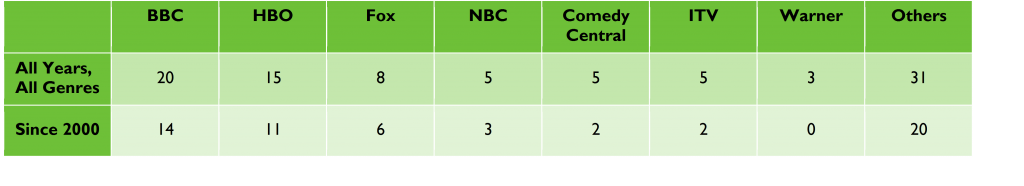

Let’s now look at some facts to test this, starting with BBC’s quality. I’ve used as my source the 100 top rated TV programmes in the IMDb database. I’ve adjusted the data to make it fair. First, I’ve removed double counting[1], which leaves 92 programmes. Second, I’ve given any remakes to the producer of the original series, for example I’ve given the US Office and House of Cards to the BBC.

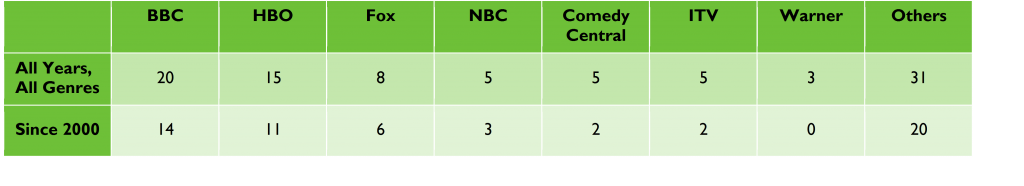

Here’s a table showing how many of the IMDb top 100 are made by each of the top production companies.

Go BBC. It produces more programmes in the top 100 than anyone else, and is also the top producer since 2000. For interest, Dr Who is in there at number 73.

Things are a tad shakier at the very top end of the ratings. BBC has 1 programme in the top 5 (Planet Earth), versus HBO’s 3 (Band of Brothers, Game of Thrones, and The Wire); and 4 of the BBC’s 5 programmes in the top 20 are David Attenborough documentaries, the other being Moffat’s Sherlock.

Things are also a little fragile if we look under the surface at what’s been made since 2000. Of the BBC’s 14 top 100 shows since 2000, 5 were by David Attenborough, and 2 were US remakes of earlier BBC originals. That’s half of the BBC’s best shows since 2000 being reliant on one brilliant 89 year old and two US studios.

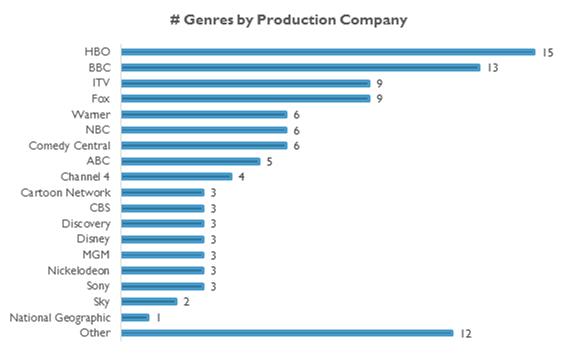

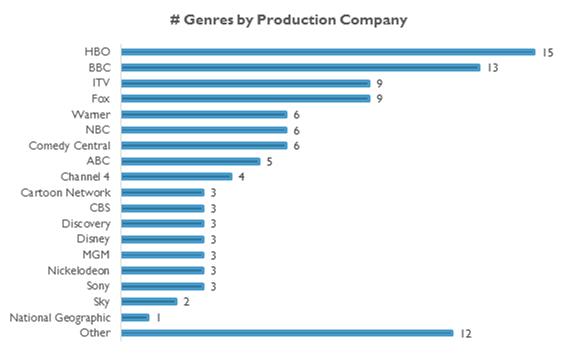

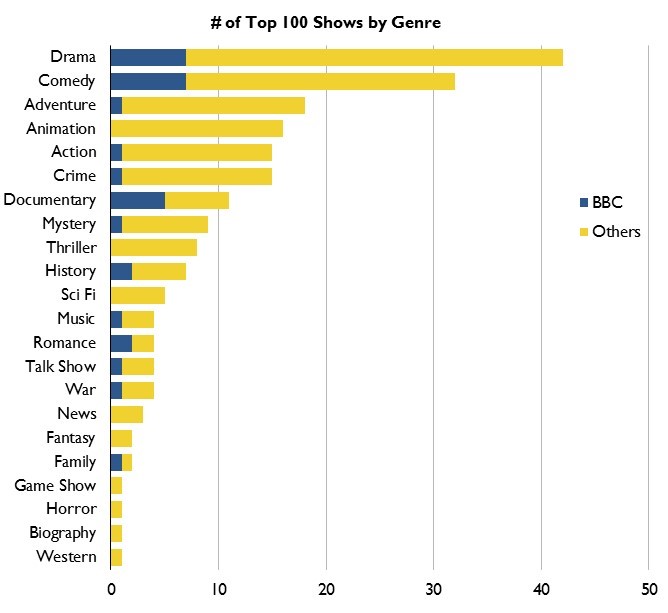

Let’s now look at variety, and whether the BBC makes programmes in genres that would be very weak if the BBC didn’t exist. The IMDb top 100 contains 22 genres, and the BBC is in 13 of them, compared to HBO’s 15, ITV’s 9, and Fox’s 9.[2]

So the BBC is there or thereabouts in having lots of variety, even if it’s not the stand out global number one. But what about the more germane point of the BBC contributing heavily to areas that other production companies don’t cover? Here’s the BBC’s number of shows compared to everyone else’s shows in each genre in the top 100.

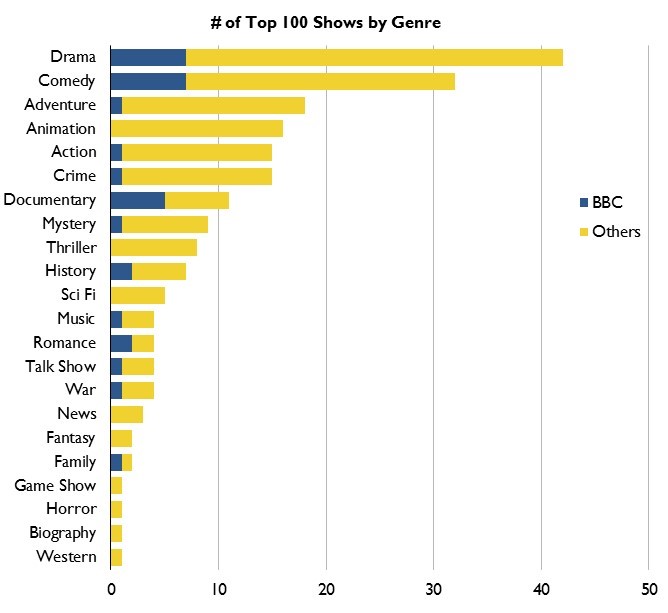

The BBC’s biggest areas are drama and comedy, which are also the most popular areas across the board. The BBC is the second biggest producer of high quality drama after HBO, and is the biggest in comedy.[3] Though this puts the kibosh on the BBC championing poorly represented genres, it does say that the BBC is making what the punters like, which seems like noble work.

The genres where the BBC really moves the dial are documentaries, with 5 of the 11 most popular, and at a pinch romance, with 2 of the 4 biggest tear jerkers. These genres would be noticeably poorer without the BBC.

So here’s what I conclude about the BBC’s quality and variety from all this:

- It makes lots of good programmes, more than any other producer in the world

- It’s good at making drama, and people like drama

- It’s very good at working with David Attenborough to produce outstanding documentaries, and is very reliant on the old fella

We can’t conclude the BBC is a good idea because we haven’t looked at the costs, or at any alternatives, but the benefits look pretty good for drama and documentary lovers.

When I look back at Steven Moffat’s claims in the article, I see what I often see from passionate advocates: he concentrates on the good stuff, ignoring the negative side of the argument, and he exaggerates a bit to tell a good story. These are important characteristics for an advocate and a believer; but we can’t take what he says as a basis to form any solid judgement and either get behind him or boo him off stage.

Our analysis also shows something else I often see in the arguments of advocates and champions: once we accept that they’re a bit biased and take off the rose tinted glasses, they often still make some excellent points. We can only see all that with confidence because we ignored pre-judgements, cleared up the thinking, and looked at the evidence. No sh*t Sherlock.

[1]Some TV series have multiple series counted separately in the database

[2]The totals look high because each show is typically in 2-4 genres. For example, Sherlock is in crime, drama and mystery.

[3]Comedy is a little deceptive because the BBC hasn’t got many comedies in the top 100 that it produced after 2000.

There’s a truism that gets passed around before Rugby World Cups, when journalists analyse the squads being selected by their national coaches. Here’s an example of it from the Guardian about the Australian squad:

Cheika’s squad hits the key metrics that have mattered most at the World Cup to date – average age and number of Test caps. The 2015 World Cup Wallabies boast a combined 1236 caps, with an average playing age of 27 years. The average team age of the last four World Cup winners was 27 (Australia, 1999), 28 (England, 2003), 27 (South Africa, 2007) and 28 (New Zealand, 2011). Of that group, the All Blacks held the most caps with 709, followed by South Africa with 668, England 638, and the 1999 Wallabies with 622. The trend is clear: experience matters. (Emphasis added.)

This journalist has followed a common line of thinking, which goes like this: these are some characteristics of people who have succeeded in the past; if we copy them then we’ll be just as successful. So you need a squad with an average age of 28 that has the most caps you can get. Sorted.

Here’s how the Hulk responded when he read the Guardian article.

By looking just at the winners, the journalist hasn’t checked himself with a simple, obvious question, which is, “What were the ages and caps of the teams that didn’t win the World Cup? Were they any different from the team that won?” He’s been guilty of survivorship bias – just looking at characteristics of successful people, assuming that those characteristics must be what made them successful, and not checking whether they did anything different from what the unsuccessful people did. He’s made a ton of other logical mistakes, but we’ll concentrate on this howler.

Does Average Age Matter?

We’ll start with how old the winning team needs to be, and the assertion that 28 is the magic number. Here’s the average age of the major nations at the World Cup in 2011, which New Zealand won[1].

- 26 – Australia, Wales

- 28 – NZ, Scotland, England, Ireland, S Africa

- 29 – France

So most teams had an average age of 28, and all but one of those teams didn’t win the World Cup. If I wanted to ram things home with some random analysis, I’d say that teams that didn’t have an average age of 28 did better than those that did. France (average age 29) came second, Australia (average age 26) came third, and Wales (average age 26) came fourth. All the others with average age 28, except NZ and Scotland, lost in the quarter finals. Scotland didn’t qualify from the group. I doubt that Tonga, average age 29, were bemoaning their excessive age as the key reason they didn’t take home the silverware.

Just so we’re not deceived by averages, the age difference between the oldest and youngest player in these teams ranged from 10 years to 15 years. Rather than coaches nurturing a cohort who reach 28 at the World Cup, it seems that players peak in their mid to late 20s but that coaches choose their best players for each position, even if they’re much older or younger. We’ll come back to this issue of having the best players once we’ve looked at whether having lots of caps is important.

Do More Caps Mean More Success?

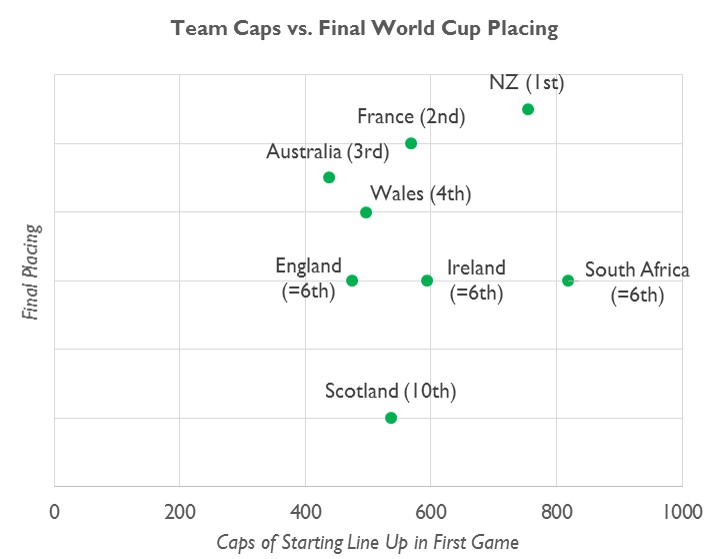

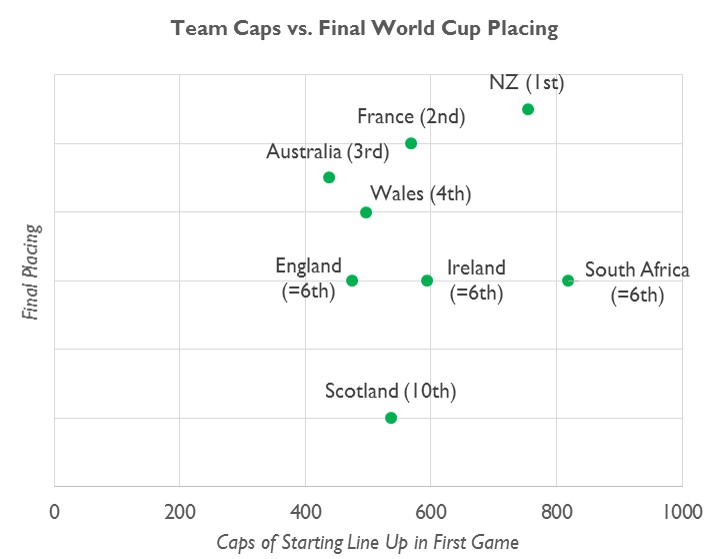

Here’s an analysis of how caps affected 2011 Rugby World Cup success. I’ve given all the quarter finalists a placing of 6th (halfway between 8th for being the worst quarter finalist and 4th for being the worst semi finalist), and Scotland 10th (just missed out on quarters by coming third in its group).

Can you see the relationship between caps and placing? No? That’s because there isn’t one. This scatter chart has an R-squared (a measure of correlation between two variables) of less than 0.02, which is pretty much the same thing as being random. Even the most hopeful, biased analyst would be embarrassed about claiming a relationship that has an R-squared of anything less than 0.5. If you do a similar analysis using matches won instead of placing, you get the same non-relationship.

The lesson from all this is that you can find yourself down some blind alleys if you just look at snippets from success stories to show you what to do. You need to think about it properly. So put down that millionaire, gold medallist philanthropist’s autobiography, take off your rose tinted glasses, and look beyond the top of the podium to see what actually distinguishes successes from failures.

What Does Seem to Matter?

I’m not going to stop here and leave rugby fans hanging by ending on what doesn’t matter. I don’t pretend to know for sure exactly what creates World Cup success, and I’m not going analyse what I suspect in this article; but here are a few facts that give us some hints:

- Since IRB rankings began in 2003, the top ranked team in the world has always won the World Cup (England in 2003, S Africa in 2007, and New Zealand in 2011), i.e. nothing magical happens at the World Cup to stop the best team winning it

- Since the World Rugby Player of the Year awards started in 2001, the country with most winners and nominations in the years since the previous World Cup, and including the World Cup year, has always won the World Cup.[2] (S Africa tied with NZ for nominations in the years leading up to 2007, which S Africa won)

- The U21 World Rugby Championship was the earliest junior world cup, and began in 2002. The team that won it 2 out of 3 times between 2002 and 2004, in that magical 7-9 years before players hit their late 20s at the 2011 World Cup, was, yes, New Zealand

- Home advantage does count, but not as much as being the best team in the world. Southern hemisphere teams are typically ranked higher than Northern, and have won 6 of the 7 World Cups to date. No Northern hemisphere team has won a home World Cup. New Zealand won both times it hosted, and South Africa won the one time it hosted. Of the Southern hemisphere World Cup hosts, only Australia hasn’t won: it lost in the final in extra time against the then top ranked team in the world, England

- Finally, it’s sport, so there’s always randomness around the edges that can make a big difference to individual matches: different weather suits different teams, referees have different interpretations, players have good and bad days, players are binned or not binned on marginal calls, game plans come off or bomb, key players get injured, and the officials miss the odd forward pass

What I take from this tiny sample of data is that the best team is made of the best players, and those players are created at least a decade before the World Cup. If you’re there or thereabouts with player quality, then you’ve got an even better chance if you’re playing at home and have a bit of luck. So it strikes me that the most important people in your country’s World Cup attempt are the people organising youth policy and player development, and the commercial team bidding to host it.

Of course, before affirming this as anything more than a supposition, I’d want to analyse it properly.

[1]I’ve used the starting line up from the first game for each team, so I’m not tempted to select matches arbitrarily. I’ve also included only the teams from the original Tri Nations and Five Nations, because I want to have a level playing field when analysing caps later.

[2] In my analysis, I gave winners double the weighting of other nominees, but that doesn’t affect the result